Mowachaht / Muchalaht First Nation’s History

The first residents of Nootka Sound were the Mowachaht and Muchalaht peoples. They had a rich existence and culture based on whaling, river fishing, hunting and foraging. They were great whale hunters, pursuing them far out to sea in whaling canoes.

In 1966 John Dewhirst and Bill Folan of Park’s Canada conducted the archaeological Yuquot Project at Friendly Cove. Evidence indicated that indigenous people had continuously inhabited the site for the last 4,300 years. In 1992 Yvonne Marshall, then of Simon Fraser University, enumerated 177 archaeological sites throughout Nootka Sound. These studies prove that Nootkan peoples had certainly inhabited the area long before the arrival of the first Europeans.

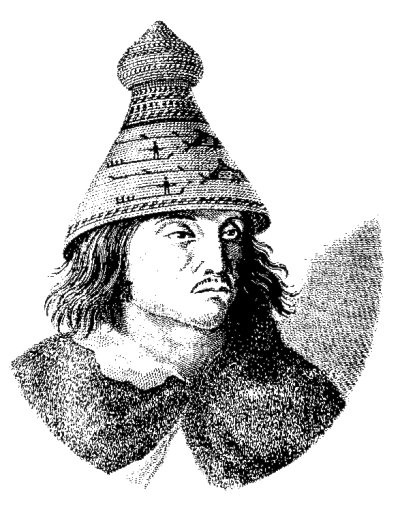

A Nootka community consisted of several distinct tribal groups, each one claiming direct descent from a known ancestor. History names Maquinna as the Nootkan Chief who met James Cook, but for generations the highest-ranking chief of the Mowachaht people bore that title, or name, “Maquinna”, a man with special rights and privileges, one holding the highest place in Mowachaht society.

Nootkan villages consisted of three groups: chiefs, commoners and slaves. The slaves being people captured during battles with other tribes, and normally being people owned only by a Chief. Members of every household accepted rank according to their relationship to the Chief, and the Chiefs ranked from highest to lowest with Maquinna as the highest ranking Chief in the highest ranking lineage group of his community.

Mobility within the kinship saw people move from house to house or even from village to village, and commoners with relatives within a household could claim residence within that household, or if they so chose, could go to live elsewhere. Therefore, in order to keep his tribe strong, the Chief had to win the respect, loyalty and support of the people below him.

The various tribal groups lived along the beach in rows of large wooden houses, each with four to six families made up of direct descendants, together with a number of their relatives by marriage. Removable planks fixed to permanent frames formed large pre-fabricated Big Houses, with the planks of the sloping roofs easily removed to allow smoke to escape, or on pleasant days to allow light and air to enter. When the tribe moved, the planks laid between canoes, became platforms on which to transport belongings and upon arrival at the new location these planks fit easily into pre-existing frames to make new dwellings in which to establish the home.

The Nootka people changed locations with the seasons, and upon the availability of the fish, berries, wild spuds, medicine roots, or bark and straws for weaving. They moved for instance to Yuquot (Friendly Cove) each February for spring and summer because of an abundance of fish, water, birds, seals, whales and sea otters. The men fished and hunted. The women gathered shellfish and herring eggs from spruce boughs placed in the water, and picked the wild berries.

In late August, when the rains began, the Nootkans left Yuquot and moved from the outer coast into the nearby inlets and rivers to catch the salmon heading upstream to spawn. These they smoked and dried for winter food, but they also gathered a variety of edible roots, and formed ripened berries into dried cakes.

Toward mid-November the families moved again, to Tahsis, their winter home, where they hunted deer and bear, and fished the rivers. When rain curtailed such activities the time came for feasting and for celebrations. By late December they were back out onto the coast to take advantage of the herring runs, and by the end of February were returning once again to Yuquot.

With the Nootkan lifestyle revolving around such seasonal marine resources, Maquinna had to make certain that he controlled property rights and resources in widely spaced areas, and this he ensured by making astute marriage alliances to cement loyalties. The Nootka held strongly to the concept of group ownership over individual ownership, with his tribe collecting berries, fish, and game on the property controlled by the tribe and giving whatever they gathered to Maquinna who then gave back most of what had been collected - including food - and thereby made the resources owned by one, but shared by all.

Skilled fishermen, the Nootka used a variety of traps, nets and tools but only chiefs and some selected commoners could hunt the California grey and humpback whales. Because this dangerous work required skill, preparations began months before the actual hunt began. The hunters not only made and repaired equipment, but also performed elaborate ceremonies and rituals. By April, with preparations complete, Maquinna declared the opening of the whaling season with he, himself, leading the hunt, and his wife conducting ceremonies and spiritual preparations that began early in the morning and ended with the eating of the whale.

The Nootka enjoyed celebrations and held them often. Some marked family and individual events as well as the opening and closing of the herring or salmon seasons. The presence of guests at the feasts and ceremonies served to validate the event and amid much singing, dancing and feasting the host Chief lavished expensive gifts on his guests as thanks for their coming. In such manner he demonstrated his wealth, generosity, and prestige. The most important and elaborate celebration, the potlatch, took place when a high-ranking Chief passed to his sons any rights he himself might possess.

First Nations Today

The Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation leadership is comprised of a Council of Chiefs. The community still follows the traditional hereditary chieftainship system. One of 14 member nations of the Nuu-chah-nulth, the Mowachaht/Muchalaht are currently in treaty negotiations as part of the Comprehensive Land Claim that was presented to the Canadian government in 1980.

Tsaxana, the main village site of the Mowachaht/Muchalaht, is situated 3 kms north of the Village of Gold River. The first construction phase occurred in 1994 with 44 single family homes, an administration building and gymnasium that included an Adult Education Centre and Day Care Facility. Ten additional residences were added in 2009. A contemporary Big House, the House of Unity, officially opened in the spring of 2011 for cultural gatherings.

Currently, the main economic activity of the community can be found in the Local Government, the forest industry and the tourism sector. The Mowachaht/Muchalaht operate the Muchalaht Marina at Ahaminaquus near the mouth of the Gold River with plans for future development. The nation also owns and manages a six rustic cabin rental business at Yuquot since 1994, offering a unique west coast experience.

One Mowachaht family still occupies Yuquot, the place most consider their homeland. This National Historic Site, the original home of Chief Maquinna and original site of the Whaler’s Shrine, was once the only Spanish settlement in Canada.

In December 1996, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada re-commemorated Yuquot, formally acknowledging the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation’s history there.

In 2006, Parks Canada and the community completed plans for Niis’Maas, an Interpretive Centre at Yuquot. The Land of Maquinna Cultural Society, a non-profit society, carries the mandate to preserve, protect and interpret the Mowachaht/Muchalaht’s cultural traditions. As part of this program, a Resource Centre at Tsaxana opened in 2006 that houses contemporary and historical artifacts, photographs, books and documents.